The “What-If” Writing Method

The “What-If” Writing Method

Sometimes when I’m writing, brain just....stops. No more ideas. No more words. Nothing. Sometimes, the solution to this problem is to simply take a break from writing and let your brain relax. Other times, though, you really are just at a block for ideas. This happened to me significantly more often than I would like, but thankfully, I’ve developed a solution that works well for me, and it’s uncreativly titled the “what-if” method.

Get a piece of paper and pen. Or a Google doc, or whatever works best for you.

Start brainstorming questions about your story, or possible “what-if” scenarios. (Ex: What if my character got framed for a crime they didn’t commit?)

Write down every single idea that comes to your head. Even if it doesn’t really work for your story. Even ones that deviate from your existing plot. Even the stupid ones. Especially the stupidest ones.

Cross out the ideas you don’t like, circle the ones that you do like.

Start coming up with answers for the questions you circled, or expand in the by coming up with more questions. (Ex: They would have to prove they didn’t commit the crime to regain their freedom. How do they prove it?)

Repeat until you have a full idea that you can work on/write with.

That’s it. That’s the whole strategy. I’ve used this a million times, and it’s gotten me out of a million cases of writers block, so hopefully it can work well for you too! Happy writing!

More Posts from Lune-versatile and Others

u know what, even if my writing isnt the BEST, i still made it all on my own. like there was a blank word doc and i filled it up with my own words, my own story. i took what was in my head and i made it a real thing. idk i feel like that alone is something to be proud of.

Okay but why aren’t more people talking about that fact that it’s literally so helpful to put together a playlist based on whatever you’re writing?

It can help for multiple reasons; ones for me would be:

It helps me outline where the story is going

It makes it feel a little more official; like I’ve got my head in the game and there’s no point in turning back now

It gives me a little sense of accomplishment

It gives me something to listen to while writing that’s less likely to distract me; and if it does, the lyrics will only help me imagine the story more

Like- 10000/10 so helpful 100% recommended this, especially if you have attention span issues or if you end up giving up on something if dopamine takes too long to come from it

Tips for writing an essay with executive dysfunction: do this.

Write out bits and pieces of the essay. When you get to a part you can’t/”don’t want to” write, put it in bold brackets. Get as much done as you can and come back in a half an hour or so!

If the executive function is still bothering you, take it one bracket at a time. Don’t delete the bracket until you’re done “filling it in,” so to speak. If you need to take more breaks or hop to the next bracket, you can do that too! Similarly, if you have a thought you want to get down but you aren’t sure how to word it, put it in bold brackets as well!

It may not “cure” the executive dysfunction or procrastination problems, but it makes writing the essay more like putting shapes in holes of the same shape. It can be a pain, but the process is a bit more streamlined and user-friendly.

I know this may not work for everyone, but as someone who has really bad executive dysfunction and problems focusing (thank you, ADHD!) this works REALLY well for me! I hope by sharing it it can help other people (with and without executive dysfunction/adhd) too! o/

How to Write Flashbacks More Effectively

Many of our favorite books include a flashback or two. They put the main story on pause and reveal things readers need to know, but how do authors decide when to use them?

These are a few tips I have about writing flashbacks effectively so you can feel confident about weaving them into your stories.

1. Create a Clear Trigger

When you walk into a kitchen and smell cookies baking in the oven, the smell might trigger a memory. Maybe it’s a happy memory of baking with your family or exchanging cookies with your friends during a holiday party.

You wouldn’t think about that memory in that exact moment without the sensory trigger. Flashbacks work the same way.

Give your character a specific trigger so it’s obvious they’re having a flashback. You shouldn’t only rely on making the flashback italicised or set off by page breaks. It will feel more expertly integrated if there’s a cause-and-effect relationship with the scene.

The trigger can also serve a purpose. Maybe your protagonist hears a car honking and has a flashback to their recent car accident. It could let the reader in on how the accident happened or what it was like. The sound being a trigger also shows readers that your protagonist hasn’t dealt with the emotional ramifications of that traumatic experience, so it’s still fresh and affecting how they live their life.

Remember, there should be a clear point of return when the flashback ends. It may not always be a second trigger, like your protagonist’s best friend calling their name. It could also be a sensory moment or experience within the flashback that makes the protagonist essentially wake up due to discomfort or becoming aware that it’s a memory.

2. Make It Plot Essential

Flashbacks are plot essential, meaning that they have to either do something for the reader or your protagonist (maybe both at the same time).

In the above example, reliving the car accident informs the reader about what the protagonist experienced before the story started.

A flashback about an ex-partner treated the protagonist in a previous relationship could motivate the protagonist to make a choice in their current relationship that they wouldn’t have otherwise. The choice propels the story in a new direction.

3. Get to the Point

It’s important to keep flashbacks brief. Readers are investing their time and energy into the story you’re telling, not the story that happened leading up to your plotline.

Extended flashbacks can also confuse readers. They may not understand when the flashback has ended, especially if the relived experience happened to your protagonist recently.

A few paragraphs to a page or two will likely be more than enough to get your flashback’s point across. If it runs longer, make a mental note to return to that particular scene when you’re in your editing phase.

-----

Flashbacks can be effective storytelling tools, but use these tips to avoid relying on them too much or in the wrong ways. If one doesn’t feel right even after you’ve worked through your initial edits, you can always take it out and work the information in by writing another present-day scene or conversation.

A Quick Guide to Foreshadowing!

Foreshadowing - a warning or indication of a future event. In literature, it is when an author provides readers with hints or suggestions as to what will happen later in the story.

Foreshadowing can be used to create tension and set expectations as to how the story will play out. Can inspire reader emotions–suspense, unease, curiosity,

Types of Foreshadowing

Chekhov’s Gun The author states something that they want you to be aware of for the future - in the eponymous example, a gun hanging on the wall in an early chapter will be used later.

Prophecy A statement to character/ reader about what will happen in the future. Although sometimes unclear at first, they normally become true by the end.

Symbolism A more abstract way of foreshadowing, often shown through things like objects, animals, images and weather. Often foreshadows change in mood, luck or behaviour.

Flashback/Flashforward When the author needs the reader to know something that happened that doesn’t fit with the current timeline. Often there will be hints/clues for things that the writer wants you to remember/pick up on later.

Red Herring A type of foreshadowing that deliberately misleads the reader. False clues such as a character finding another suspicious, etc., may lead you to believe one thing when, in reality, they will have done nothing wrong

Tips and Tricks for Effective Foreshadowing!

Don’t foreshadow too obviously - signpost rather than state! Arouse suspicion, but keep them guessing!

If you make a promise, keep it!

The bigger the twist, the earlier it should be foreshadowed! Foreshadowing too soon is essentially a spoiler

Keep foreshadowing in moderation

Use beta-readers - sometimes our foreshadowing feels so obvious to us but it may not to other people who aren’t as close!

Writing Notes: Outline

Outline - a skeletal representation of the sequence of the main ideas in your essay.

The sequence of ideas/topics also serves as a guide for the reader(s) of your paper.

2 Purposes of an Outline

For You as a Writer (this is the “working outline”)

You may draft a working outline in order to organize the sections of your paper as you list the major ideas/topics you plan to discuss.

You may add minor topics and supporting details as your research continues.

In the research and drafting processes, you may need to revise the information included in your working outline as new information comes to light.

For Your Instructor (this is the “final outline”)

The most important aspect of the final outline is that it is truly representative of your actual paper.

If a topic is in your outline but not adequately discussed in your paper, revision is necessary.

To serve as a guide for the reader, the final outline must accurately reflect the content of your paper.

About the Working Outline

The working outline does not need to be written in any specific format.

It is for your own use, an informal rough draft of tentative information that you may use or discard later.

You may write a working outline in whatever form seems most helpful for you.

By the time you have finished your research and begun your paper, you should have a nearly complete outline to edit and use as your final outline.

About the Formal Outline

The standard format for a formal outline includes large Roman numerals for the main headings, capital letters for subtopics and Arabic numerals for the sub-subtopics.

To find specific information regarding correct spacing and alignment, consult your university's handbook.

Example

OUTLINE

Thesis Statement: There are benefits as well as drawbacks to purchasing a home.

I. Benefits of purchasing a home

A. Financial investment B. Personal privacy

II. Drawbacks to purchasing a home

A. Financial commitment B. Costly maintenance

Things to Consider About Outlines

Thesis Statement

Most outlines begin with the thesis statement, aligned to the left and placed directly below the heading (Title) of your outline.

Sentence Outline OR Topic Outline

Consistency is the key to writing your outline.

If your outline is in sentence form, all parts of it (major topics, minor topics, supporting details) must be in sentence form.

If your outline is written in words, and phrases, all of it must be in that form.

The main point to remember is that your outline will be one or the other, all sentences or all words and phrases, not a combination of both.

Paired Headings

If you have a I., you must have at least a II. If you have an A., you must have a B.

If you have a 1., you must have a 2.

There is never a division without at least two headings, although you may have several more than two.

Comparable Numerals or Letters

Like headings are also of equal significance to your paper.

The B or C following an A is of comparable importance to the A.

If the paired headings do not seem aligned, one being a minor point and the other a major area of discussion, you may need to move headings and subheadings around in the working outline to create smooth transition of ideas and information.

Coherence

Your outline will reflect the progression of ideas in each section of your paper, from major topics to minor topics to supporting details or further information.

In organizing your outline, you should find that you have grouped topics in a logical order, and you will be able to see at a glance if you have done so.

Source ⚜ Writing Notes & References

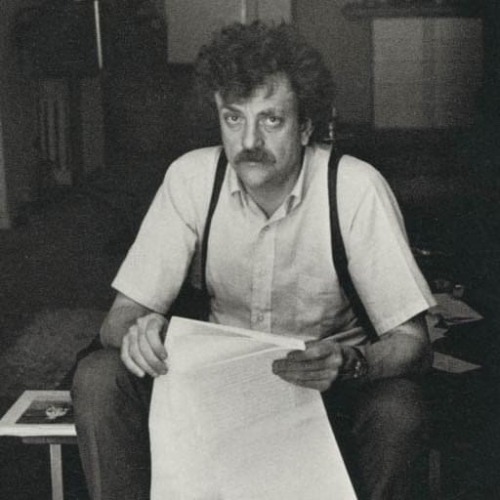

In 2006 a high school English teacher asked students to write a famous author and ask for advice. Kurt Vonnegut was the only one to respond - and his response is magnificent: “Dear Xavier High School, and Ms. Lockwood, and Messrs Perin, McFeely, Batten, Maurer and Congiusta:

I thank you for your friendly letters. You sure know how to cheer up a really old geezer (84) in his sunset years. I don’t make public appearances any more because I now resemble nothing so much as an iguana.

What I had to say to you, moreover, would not take long, to wit: Practice any art, music, singing, dancing, acting, drawing, painting, sculpting, poetry, fiction, essays, reportage, no matter how well or badly, not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming, to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow.

Seriously! I mean starting right now, do art and do it for the rest of your lives. Draw a funny or nice picture of Ms. Lockwood, and give it to her. Dance home after school, and sing in the shower and on and on. Make a face in your mashed potatoes. Pretend you’re Count Dracula.

Here’s an assignment for tonight, and I hope Ms. Lockwood will flunk you if you don’t do it: Write a six line poem, about anything, but rhymed. No fair tennis without a net. Make it as good as you possibly can. But don’t tell anybody what you’re doing. Don’t show it or recite it to anybody, not even your girlfriend or parents or whatever, or Ms. Lockwood. OK?

Tear it up into teeny-weeny pieces, and discard them into widely separated trash recepticals. You will find that you have already been gloriously rewarded for your poem. You have experienced becoming, learned a lot more about what’s inside you, and you have made your soul grow.

God bless you all!

Kurt Vonnegut

Nimbus Publishing and Vagrant Press Goose Lane Editions Breakwater Books Ltd. The Acorn Press Bouton d'or Acadie Canada Council for the Arts | Conseil des arts du Canada

How to Write a Death Scene

So, you want to write a death scene that hits your readers hard, right? Something that sticks with them, makes them feel something real?

First, give the death meaning. You can’t just toss in a death for the shock factor and call it a day. Even if it’s sudden or unexpected, the death has to matter to the story. Think about how it changes things for the characters who survive. Does it mess with their relationships? Their goals? Make sure this moment sends ripples through the rest of your plot. It’s gotta affect everything that happens after, like an emotional earthquake.

Then, think about timing. You don’t want to drop a death scene at the wrong moment and ruin the vibe. If it’s part of a big heroic moment or a heartbreaking loss in the middle of the story, it should feel earned. The timing of the death decides how your readers will react, whether they feel relief, gut-wrenching sorrow, or are totally blindsided. The right moment makes all the difference.

Next up, focus on the characters’ emotions. Here’s the thing, it's not always the actual death that makes a reader cry, it's how everyone feels about it. How do the characters react? Is the person dying scared, or are they at peace? Are the people around them in shock, angry, or just completely destroyed? You need to dive deep into these emotions, because that’s where your reader connects.

Make sure to use sensory details to pull readers into the scene. What does it feel like? The sound of their breathing, the stillness when they’re gone, the way everything feels heavy and wrong. Little details make the death feel real and personal, like the reader is right there with the characters, feeling the weight of the moment.

If your character has the chance, give them some final words or actions. What they say or do in those last seconds can really hit hard. Maybe they share a piece of advice, ask for forgiveness, or try to comfort the people around them. Even a simple gesture, a smile, a touch, a last look can leave a lasting impression. This is your last chance to show who this character was, so make it count.

Finally, don’t just stop when the character dies. The aftermath is just as important. How do the survivors deal with it? Does your main character fall apart, or do they find a new sense of purpose? Are there regrets? Peace? Whatever happens next should be shaped by the death, like a shadow that never quite goes away. Let your characters carry that weight as they move forward.

For questions or feedback on writing materials, please send me an email Luna-azzurra@outlook.com ✍🏻

An aye-write guide to Showing vs. Telling

I’ll bet that if you’ve ever taken an English class or a creative writing class, you’ll have come across the phrase “Show, don’t tell.” It’s pretty much a creative writing staple! Anton Chekov once said “ Don’t tell me the moon is shining. Show me the glint of light on broken glass.” In other words, showing should help you to create mental pictures in a reader’s head.

Showing helps readers bond with the characters, helps them experience the emotions and action more vividly, and helps immerse them in the world you have created. So “show, not tell” is definitely not bad advice - in certain circumstances. But it has its place. More on that later.

So How do I Show?

Dialogue

Thoughts/Feelings

Actions

Visual Details

So instead, of telling me “He was angry”, show me how his face face flushes red, how his throat tightens, how he slams his fist, how he raises his voice, how his jaw clenches, how he feels hot and prickly, how his breathing gets rapid, how his thoughts turn to static, etc.

Instead of telling me “The cafeteria was in chaos”, you could show me someone covered in food and slowly turning crimson, children rampaging under the feet of helpless adults, frenzied shouting, etc.

Handy Hint! Try to avoid phrases like “I heard”, “I felt”, “I smelled”, etc. These are still “telling words” (also known as filters) and may weaken your prose, as your readers could be taken out of the experience and you may lose their attention.

Is Showing Always The Right Thing to Do?

No! Absolutely not! Showing is not always right and telling is not always wrong! It’s important to develop the skill and instinct to know when to use showing and when to use telling, as both can be appropriate in certain occasions.

So, “Show, don’t tell” becomes “Show versus tell”.

What is Showing and Telling?

Showing is “The grass caressed his feet and a smile softened his eyes. A hot puff of air brushed past his wrinkled cheek as the sky paled yellow, then crimson, and within a breath, electric indigo”

Telling is “The old man stood in the grass and relaxed as the sun went down.”

Both of these excerpts are perfectly acceptable to use in your writing! But both do different things, although their meanings are pretty much the same. The first example is immersive, sweeping, visual, engaging. The second example is much more pared back and functional. But both have their places in prose!

Telling is functional. Think about when you tell people things. You tell your children dinner is ready. The news reporter tells you there’s a drop in crime rates. Your best friend tells you she’ll be late because her car broke down on the way to yours. These are brief and mundane moments in everyday life.

So, do these deserve multiple paragraphs with sensory detail and action/feeling/thought for every little thing? Do you need to spend an entire paragraph agonising over a minor detail when there’s a sword dangling (physically or metaphorically) over your MC’s head? No. And I’ll explain why.

When To Use Telling

As before, telling is functional. It’s brief. It’s efficient. It gives a gist of a situation without getting bogged down in detail.

Showing is slow, rich, expansive, and most certainly not efficient!

Here’s an example of some telling:

“Years passed, and I thought of Emily less and less. I confined her to some dark dusty corner of my brain. I had to elbow my memories of her to the side. I was too busy with other things. Finishing school, then university a year later. Life was full and enjoyable. But then, one dark cold September night…”

You can’t show this example, unless you wanted to waste page after page of your MC waking up, going through everyday life, to get to the point your actual story started. If you do that, you will likely kill off any interest a reader would have in your novel and likely, your book itself.

Summing Up

Showing:

Should be used for anything dramatic

Uses thoughts, feelings, dialogue, action, and visual detail

Will likely be used more than telling

Telling:

Can be used for

Delivering factual information

Glossing over unnecessary details

Connecting scenes

Showing the passage of time

Adding backstory (not all at once!)

-

finalpan liked this · 7 months ago

finalpan liked this · 7 months ago -

robyn-reliant liked this · 7 months ago

robyn-reliant liked this · 7 months ago -

solarppages liked this · 8 months ago

solarppages liked this · 8 months ago -

couchbo0yz liked this · 8 months ago

couchbo0yz liked this · 8 months ago -

fancyfauns reblogged this · 8 months ago

fancyfauns reblogged this · 8 months ago -

sugargalaxies reblogged this · 8 months ago

sugargalaxies reblogged this · 8 months ago -

fancyfauns liked this · 8 months ago

fancyfauns liked this · 8 months ago -

theeverlastingspirit reblogged this · 8 months ago

theeverlastingspirit reblogged this · 8 months ago -

theeverlastingspirit reblogged this · 8 months ago

theeverlastingspirit reblogged this · 8 months ago -

theeverlastingspirit liked this · 8 months ago

theeverlastingspirit liked this · 8 months ago -

caramelpenguin reblogged this · 8 months ago

caramelpenguin reblogged this · 8 months ago -

lemon-spruce reblogged this · 1 year ago

lemon-spruce reblogged this · 1 year ago -

unipdresep liked this · 1 year ago

unipdresep liked this · 1 year ago -

disabledbisexualfroggy liked this · 2 years ago

disabledbisexualfroggy liked this · 2 years ago -

amblogging liked this · 2 years ago

amblogging liked this · 2 years ago -

romenna liked this · 2 years ago

romenna liked this · 2 years ago -

lune-versatile reblogged this · 2 years ago

lune-versatile reblogged this · 2 years ago -

fates-journal liked this · 2 years ago

fates-journal liked this · 2 years ago -

your-averagewriter liked this · 2 years ago

your-averagewriter liked this · 2 years ago -

angel-forever liked this · 2 years ago

angel-forever liked this · 2 years ago -

angel-forever reblogged this · 2 years ago

angel-forever reblogged this · 2 years ago -

kazekis liked this · 2 years ago

kazekis liked this · 2 years ago -

shyjellyfishfan liked this · 2 years ago

shyjellyfishfan liked this · 2 years ago -

m1lks0d4 liked this · 2 years ago

m1lks0d4 liked this · 2 years ago -

rowena-moon-moon liked this · 3 years ago

rowena-moon-moon liked this · 3 years ago -

alidevile liked this · 3 years ago

alidevile liked this · 3 years ago -

eastofeeeden liked this · 3 years ago

eastofeeeden liked this · 3 years ago -

appletreebunny liked this · 3 years ago

appletreebunny liked this · 3 years ago -

dreamer-101 reblogged this · 3 years ago

dreamer-101 reblogged this · 3 years ago -

dreamer-101 liked this · 3 years ago

dreamer-101 liked this · 3 years ago -

woodlandmouth liked this · 3 years ago

woodlandmouth liked this · 3 years ago -

waywardimpalawriter reblogged this · 3 years ago

waywardimpalawriter reblogged this · 3 years ago -

waywardimpalawriter liked this · 3 years ago

waywardimpalawriter liked this · 3 years ago -

acecase reblogged this · 3 years ago

acecase reblogged this · 3 years ago -

acecase liked this · 3 years ago

acecase liked this · 3 years ago -

gamingaquarius reblogged this · 3 years ago

gamingaquarius reblogged this · 3 years ago -

wrist-writer12 liked this · 3 years ago

wrist-writer12 liked this · 3 years ago -

imdoinrealbadk liked this · 3 years ago

imdoinrealbadk liked this · 3 years ago -

aisaj liked this · 3 years ago

aisaj liked this · 3 years ago -

claibin liked this · 3 years ago

claibin liked this · 3 years ago -

bright-weasel liked this · 3 years ago

bright-weasel liked this · 3 years ago